Industrial living: Community activism and environmental public health in neighborhoods on the precipiceNote: I wrote this story as a final project for my computer-assisted reporting class. As part of the project, I juxtaposed the location of TRI sites with race and income data for Colorado using GIS software. Jump to the images.

December 6, 2008

Across the street from a chemical distribution company and a church, a woman waits for the bus with a toddler in a stroller as semi-trucks rumble by on East 42nd Avenue.

Welcome to Northeast Park Hill, where houses hug one of the Denver's densest industrial areas, blurring the line between commerce and home comforts.

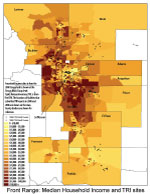

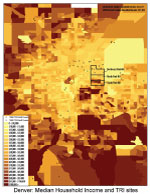

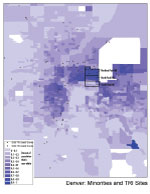

The EPA's Toxic Release Inventory program requires facilities using toxic chemicals - from lead to chlorine gas to plastic additives that mimic hormones - to file yearly reports on materials they discharge into the water, land and air. In densely populated metro Denver, residential neighborhoods border industrial areas and clusters of TRI sites, with little or no space between. Many neighborhoods with multiple TRI sites - like Swansea Elyria, Globeville, Commerce City and Northeast Park Hill - are low-income.

Environmental justice groups like Groundwork Denver are helping local communities improve their environmental health, but they can only assist with problems that are brought to their attention. Often, environmental risks go unnoticed because the data is difficult to interpret or the threats are invisible.

The greater Park Hill area, stretching from Colfax Avenue on the south past I-70 to the edge of Adams County, includes one of Denver's richest neighborhoods and one of its poorest.

Over the course of 12 blocks - slightly more than a mile - the average household income shifts from $88,470 in South Park Hill to $37,468 in Northeast Park Hill, which includes many TRI sites. Denver's average household income is $55,129, according to the 2000 US Census.

Heading north on Dahlia Street, the houses change from Queen Ann and brick to cream and powder-blue siding to single-story ranch-style. On the corner of East 38th Avenue and Glencoe Street, a pile of rusted steel I-beams sits in the parking lot of an abandoned gas station. A few blocks from I-70, warehouses dominate and barbed-wire fences guard chemical tanks and forklifts.

"Smith Road, they call that the city limits," said Greg Rasheed, executive director of the Greater Park Hill Community.

The transition from high-income residential to low-income residential to heavy industrial is somehow both seamless and abrupt.

Although trucks and rail cars have replaced sedans and SUVs, pockets of neighborhood - a pet day care center, cafe and Planned Parenthood clinic - nestle between the Colorado Container Company and Univar, a chemical manufacturer.

Smith Elementary School is just one block from several TRI sites.

"Because children are continually growing and developing, we think of them as high risk populations," when it comes to exposure to pollutants, said Shelly Miller, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Colorado who studies air pollution.

But the limits for exposure in the workplace are designed for healthy adults, not children.

"People working with occupational safety and health," said Miller, "go out and make measurements to make sure that workers aren't being exposed to high concentration." The standards set, "are going to be too high for children or old people."

Air pollution is a potential health threat for those living near industrial areas. But how close is too close?

According to the most recent TRI reports, facilities in Northeast Park Hill emit toluene, xylene, ethylbenzene - all volatile organic compounds, rapidly evaporating chemicals with dangerous health and environmental effects - into the air. Less than two miles away in Commerce City, plants are spewing benzene, a known carcinogen, and chlorine, a poisonous gas used as a weapon in World War I.

"I would be concerned with some of these," said Miller, looking at the list of chemicals from TRI reports. "There are definitely carcinogens. I think if the neighbors knew...but it depends on how much."

The reality is that the often neighbors aren't concerned, or often don't know what kinds of chemicals are being released in their backyards.

"To be honest with you," said Rasheed, "the industrial area doesn't really affect the neighborhood. The neighborhood is separate."

The GPHC was formed in the 1960s to address the issue of white-flight and foster good relationships among the neighborhood's culturally and racially diverse residents. Their logo is a composite of two faces - one white, one black - who share a common eye.

"What we work on here is everything from zoning issues, housing issues, criminal justice issues, senior issues, youth issues, anything involving the neighborhood," Rasheed said.

Anything, that is, that captures the community's attention.

Problems that are brought to the GPHC typically demand notice - like the delivery truck driver blasting music at 8 a.m. or the neon restaurant sign that was blinking until dawn.

If citizens can't see, smell or hear environmental hazards, they probably won't be raised in the community or local government. Toxins and carcinogens are especially difficult to notice, considering, "you can get cancer to something you were exposed to years before," said Miller.

Two glaring environmental and health concerns in the Northeast Park Hill are the Holly and Dahlia shopping centers. One burned down, the other was demolished, and both are, "impossible to miss," said Rasheed.

Although the block-sized hole between Dahlia Street and Elm Street at East 35th Avenue and the charred, fenced-in ruins at East 33rd Avenue and Holly Street are glaring enough to cause concern, the community is struggling with how to proceed.

When the Dahlia Street shopping center was demolished, asbestos was found. "Supposedly they took care of it so that it wouldn't affect the neighborhood," Rasheed said. "But we don't know if the asbestos was really cleaned up or not."

Rasheed is also concerned with Stapleton, directly east of Park Hill, built on top of a former airport. "You've got runways out there that are under homes," he said. "How much pollution is still there? No one's going to report on that."

According to the EPA, the purpose of the TRI program is to give citizens and community groups like GPHC the information they need to hold companies and governments accountable for environmental risks.

But even when environmental data is there, interpreting it is difficult.

Wendy Hawthorne, executive director of the environmental justice group Groundwork Denver, says having EPA data accessible to the public is"a great idea."

Using it is another story.

"You would have to have a high technical capacity to wade through this stuff," Hawthorne said.

Many neighborhood associations are volunteer-run. In order to analyze TRI or air-quality data, they would need to find an environmental consultant willing to volunteer to assess potential health threats.

That's where organizations like Groundwork Denver can help communities.

"We work with low-income groups in Denver to improve the urban environment," said Hawthorne. They do this by, "organizing resources and volunteers to actually clean things up, to make it happen, as opposed to just writing letters," she said.

In low-income communities, said Hawthorne, "fewer people are members of traditional [environmental] groups, but in terms of the urban environment they care just as much."

Old growth stands and wolf populations may not resonate, but clear air, water and soil do - just as much if not more than in high-income communities.

Groundwork Denver has helped communities in Swansea, Sunnyside and Commerce City. Northeast Park Hill is one neighborhood that Groundwork Denver has yet to work with, although they've considered the idea. They also assisted Globeville residents with Superfund sites, an initiative that was driven by the local community.

"The residents really made that happen," said Hawthorne.

Hawthorne hopes that future Groundwork Denver projects - some of which are funded by the EPA - will come from requests by groups like GPHC.

"A community coming to use and asking for our assistance is the idea," said Hawthorne.

The tools a low-income neighborhood like Northeast Park Hill needs to tackle environmental health and air-quality issues are there: a strong neighborhood association, environmental data, and local activist groups. But the way those tools are set-up, residents are the ones that need to raise concerns about environmental health before any work is done.

Other issues - like health care, housing, and education - overshadow environmental concerns in neighborhoods like Northeast Park Hill. Who, then, will take on the role of investigating environmental risks?

Miller has some advice for individuals or community groups looking to wade through the overwhelming mass of environmental information that is publicly available: "Pick one or two compounds to get your feet wet."

Benzene, for example.

"Read up about what the health issues are, what the concentration for risk is," she said. "Then, once you get your hands around the terminology and health effects, talk to regulators like the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, that could give you the knowledge so that you could start to look at other things."

There's no doubt the residents of Park Hill would rally around an environmental health initiative.

"If [GPHC] says we need something, people do come through. They take personal responsibility," said Rasheed.

But first, someone has to start digging.